You know the bottles. Cognac. Armagnac. Calvados. Grappa. Pisco. Metaxa. Chacha.

All proudly waving the brandy flag, all claiming their piece of liquid history. But where does this whole “burnt wine” thing actually come from, and how did it evolve into one of the most diverse spirit categories on the planet? Let’s dig in.

The Basics

Let’s fix this in our minds: Brandy is any strong alcoholic drink obtained by distilling wine, pomace, fruit juice, or any by-products thereof. Grape-based spirits are considered separately from fruit-based ones, which must be labeled explicitly as “fruit brandy.”

Its ancestor could be considered the earliest distillates from fermented fruit juices, mentioned by the ancient Greeks and Romans as well as Asian cultures. Historically, we owe the drink’s modern form to Dutch merchants. These resourceful gentlemen bought wine in southern France and, naturally, took several barrels home. To keep the wine from spoiling, they distilled it and called the result “brandewijn” – “burnt wine.” It was common to dilute it with water before drinking, but many enjoyed it neat. Consumers noticed that barrel-aged spirits (because of the long journey into casks) developed a more elegant bouquet of flavors and aromas, and connoisseurs emerged. The English, finding the Dutch name unwieldy, simplified it to “brandy.”

Regulations (a.k.a. Why your “brandy” might not be brandy at all)

Depending on where you are in the world, “brandy” might mean very different things:

- EU law: Must be made from distilled wine (or fermented fruit juice for fruit brandies) and aged in oak for at least 6 months (often longer). Grape brandies must have a minimum 36% ABV.

- US law: Must be distilled from fruit wine to less than 95% ABV, bottled at not less than 40% ABV. Ageing isn’t strictly required for all fruit brandies.

- Many countries have their own protected designations (like Cognac or Pisco) with stricter rules.

The French heavyweights

Cognac

There are two origin stories – one French, one Italian. The French tell of a knight-winemaker who caught his wife with a lover, killed them both, and later, after a dream involving the devil (don’t ask), decided to double-distill his wine. The Italians insist they invented wine distillation first and that their ambassador gifted French nobility the very first grape brandy.

In reality, it’s simpler. Dutch traders (see above) bought wine from around the town of Cognac, on the Charente River. Thanks to endless vineyards and a flawless climate, the region’s wines became famous across Europe. The Dutch taught locals how to distill and prospered – until the mid-17th century, when high tariffs were introduced on ships entering French ports. This spurred the growth of the French navy, and “brandy from Cognac” began appearing frequently on merchant ships.

By the late 18th century, England was the main customer, with reduced export duties. Production boomed, and by the mid-19th century, the spirit had taken its official name from the town of Cognac. It also began to be bottled, encouraging people to drink it neat. Unfortunately, the phylloxera plague of the 1890s wiped out the region’s vineyards, and recovery took decades. A true rebirth came in 1909, when Cognac received its AOC status.

How it’s made

- At least 90% of the grape must be Ugni Blanc (most popular), Folle Blanche, and Colombard grapes. The remaining 10% can come from a few other approved varieties.

- Double distillation in Charentais copper stills.

- Aged in oak barrels from Limousin or Tronçais forests for at least 2 years.

Classifications:

- VS – youngest spirit aged at least 2 years.

- VSOP – youngest spirit aged at least 4 years.

- XO – youngest spirit aged at least 10 years.

Six crus (terroirs): By law, Cognac comes only from six crus (Grande Champagne, Petite Champagne, Borderies, Fins Bois, Bons Bois, Bois Ordinaires) – each with its own style and prestige level.

The Older Brother – Armagnac

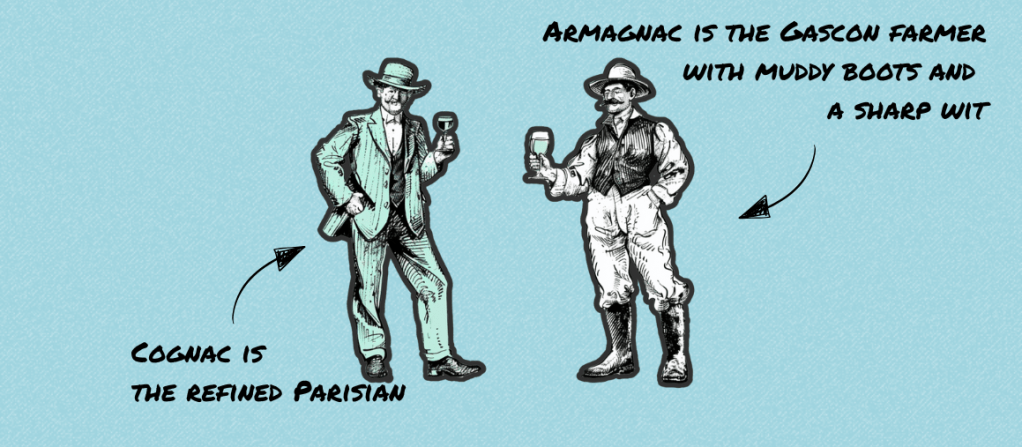

The French love to say: “Cognac we gave to the world, Armagnac we kept for ourselves.” And it’s true – Armagnac appeared several centuries before Cognac but has never been widely popular abroad. If Cognac is the refined Parisian, Armagnac is the Gascon farmer with muddy boots and a sharp wit.

Its birthplace, Gascony, has limited access to the sea, making export tricky. First mentioned in the mid-14th century, it may have been created by a duke or a nobleman who stored grape spirit in Gascon oak barrels – as with all famous drinks, legends abound.

Initially, Armagnac was an unaged eau-de-vie consumed locally as medicine and never exported. That changed when Bordeaux winemakers, afraid of competition from other regions, blocked maritime trade for foreign wines. Gascons, thinking smart, distilled their wine into spirit – the ban didn’t apply. Armagnac slowly gained fame, and over time, it was stored in black Gascon oak casks to ensure a steady cellar supply of quality spirit.

Like Cognac, it suffered from phylloxera, later gaining AOC protection and its own regulatory body.

How it’s made

- Along with Cognac’s Ugni Blanc, Folle Blanche, and Colombard, Armagnac uses Baco 22A – a rare hybrid variety.

- Distillation season ends March 31.

- Single distillation in a continuous Armagnac alembic (sometimes Cognac-style double distillation, but purists frown on it).

- Made from grapes of a single year.

- Usually stronger – 40–50% ABV.

- Always aged in black Gascon oak.

Classifications:

- Armagnac – aged 2–5 years.

- Vieil Armagnac – youngest spirit at least 6 years.

- Vintage – single year.

- Blanche d’Armagnac – unaged.

Three regions: Bas-Armagnac (light, fruity), Tenareze (complex, long-aging), Haut-Armagnac (mostly young spirits).

Calvados

Head north to Normandy, swap grapes for apples (and pears), and you get Calvados. Distilled from cider in either pot stills or columns, then aged in oak. The result? Fresh, fruity, with that unmistakable baked-apple vibe.

And here’s a fun fact – the French actually drink more Calvados than Cognac or Armagnac. In fact, over the last 50 years, its export share has jumped from 17% to 50%. Not bad for an apple brandy from Normandy, right?

A Short History

While grape-growing was the main livelihood in southern France, the northern farmers of Normandy were busy with livestock and agriculture. The climate wasn’t great for grapes, and strict taxes made things even worse for the few vineyards that did exist. So instead, they planted apple orchards everywhere.

By the 11th century, Normans were making cider – something to unwind with after a hard day’s work. For centuries, it was mostly a local drink; wine remained the national favourite.

Fast forward about 500 years, and locals wanted something stronger. Enter apple brandy. The first written record comes from Gilles de Gouberville’s diary, noting the distillation of apple cider.

As for the name “Calvados,” there are two main theories.

- The French version: It comes from the Latin “Calva Dorsa” (“bald coast”), a name used for part of Normandy’s shoreline.

- The Spanish version: A ship called San Salvador wrecked off Normandy’s coast. The locals mangled “Salvador” into “Calvador,” and eventually “Calvados.” Spanish sailors were known for distilling skill – and for telling great stories.

By the mid-18th century, the French royal council had formalised production rules for Normandy’s apple brandy. Decades later, the drink officially adopted the name “Calvados” – possibly thanks to those same Spanish shipwreck tales.

For a long time, it stayed in the shadow of grape brandies, mostly consumed in the north. Then phylloxera hit France’s vineyards, and suddenly Calvados became wildly popular. Predictably, fakes appeared, sparking years of legal battles. In 1942, Calvados finally earned its AOC status, securing its place as Normandy’s pride.

How It’s Made

- Apples: Over 350 authorised varieties, bred specifically for cider-making. They’re divided into four flavour categories – bitter, sweet, sour, and bittersweet. Only hand-picked fruit is allowed; windfalls are banned. Pears are also permitted (about 50 varieties).

- Harvest: Late autumn. The fruit is washed in spring water, dried, then pressed for juice.

- Fermentation: Around 5 weeks of natural fermentation, producing cider at 4–6% ABV.

- Distillation: Two methods are allowed – double distillation in Charentais alembics (like Cognac) or continuous distillation in a column still.

- Aging: In oak barrels, traditionally French oak. New barrels first, then older ones for complexity. Master blenders then combine different ages into a unique blend.

The AOCs of Calvados

- Calvados AOC – The largest region, producing a wide range of styles and quality.

- Calvados Pays d’Auge AOC – The smallest and most prestigious; only double distillation and typically long aging.

- Calvados Domfrontais AOC – The youngest; famous for pears, which make up about 30% of the spirit. Less than 1% of all Calvados.

Aging & Labelling

- Fine, VS, Trois Pommes – Minimum 2 years.

- VSOP, VO, Vieille Réserve – Minimum 4 years.

- XO, Extra, Napoléon, Hors d’Âge – Minimum 6 years.

For today that’s all guys!

Thank you for reading, it was quite big piece. In next part we will speak about another European brandies.

If you find our project useful – please support us with subscription

Stay boozy, stay nerds

Leave a comment